Nest etter Shakespeare er han verdens mest fremførte dramatiker. Men la oss skru klokken tilbake og se hva som tente gnisten i ham …

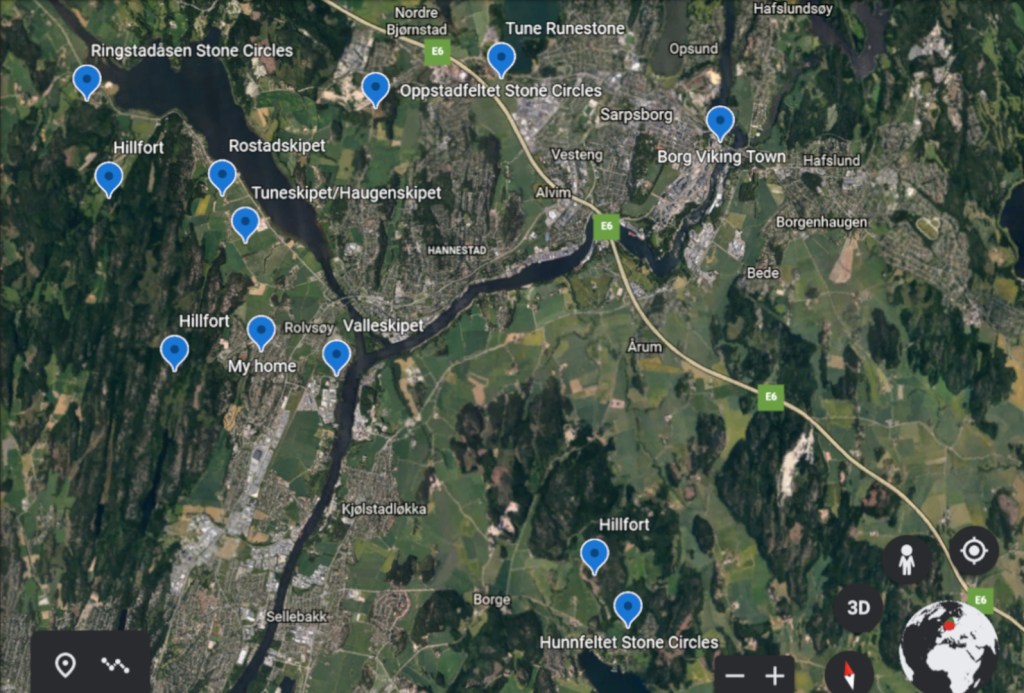

22. november 1797

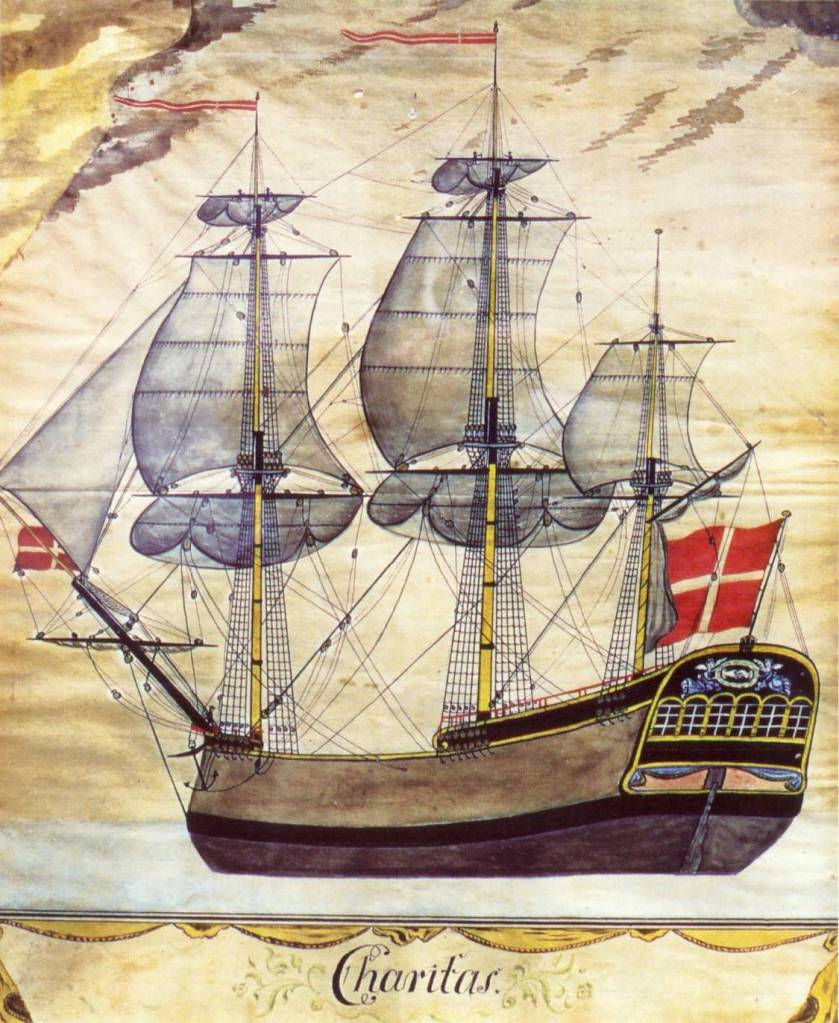

Det er mørkt og kaldt, og det herjer en voldsom storm fra sydøst. Den 32 år gamle skipsrederen og kapteinen Henrik Ibsen er på vei hjem fra London da han og mannskapet hans oppdager faren. Lyden av bølger som slår mot grunner og skjær. De forstår at de må snu, men det er ikke lett å trosse pålandsvinden og den sterke strømmen.

Om bord på «Caritas» kjemper de fortvilet idet skipet treffer land med et brak. Treverk splintres mot hard granitt. Mesanmastene ryker over bord. Deler av de øvre dekkene går også med idet bjelkene gir etter. Noen minutter senere legger det knuste vraket av «Caritas» seg omsider til ro på 30 meters dyp.

Denne natten drukner Henrik Ibsen og hele mannskapet hans på 15 mann i det iskalde vannet utenfor Hesnesøya ved Grimstad. Og tragedien er et faktum.

Tiden går, men minnet består …

29. november 1843

Førtiseks år etter skipsforliset legger båten «Lykkens Prøve» til ved bryggen i sørlandsbyen Grimstad. Nå stiger 15 år gamle Henrik Ibsen i land, klar til å stå på egne ben, noen få kilometer fra der hvor hans farfar forsvant i havet.

I 1843 er Grimstad en liten by på om lag 800 innbyggere, der de fleste familiene bor i egne hus med en liten hage. Ellers har byen tollstasjon, postkontor, sparebank, sorenskriver, distriktslege, jordmor og apotek. Ingen kirke annet enn Fjære kirke. Heller ikke avis eller bibliotek. Kun et privat leseselskap der medlemmene kan låne bøker.

Apoteker Jens Arup Reimann har nettopp startet forretning i Storgaten. Der begynner ynglingen Henrik Ibsen som apotekerlærling, og apotekeren slipper ham bokstavelig talt inn i familiens hjem og behandler ham nærmest som sin egen sønn.

I første etasje er det to værelser, bestående av apotekerlokalet og familien Reimanns stue. Apotekerlokalet fungerer også som postkontor.

I andre etasje finnes det tre sammenhengende soveværelser. Henrik får ligge i det midterste sammen med de tre eldste guttene. I det ytterste sover ekteparet Reimanns med de yngste barna, og i det innerste de to tjenestejentene.

Opprinnelig hadde Henrik vokst opp i et av hjembyen Skiens overklassehjem, med god plass til både tjenestefolk og gjester. Men i de siste årene hadde familiens boliger krympet i takt med den krympende formuen. Nå er de fleste eiendommene solgt, og farens advokatvirksomhet står uten oppdrag. For akkurat nå er det mange i overklassen som sliter med økonomien, og fremtidsutsiktene ser dermed dystre ut.

At Svaneapoteket i Skien overlevde det meste, hadde Henrik og kameraten hans sett.

Å gå i apotekerlære syntes derfor å være et trygt valg.

Hos familien Reimann lærer Henrik alt fra det grunnleggende om planters medisinske egenskaper til kunsten å preparere heftplaster, samt litt dokterlatin. Men det er ikke lett å studere til artium med en skokk unger rundt seg. Ofte blir Henrik sittende oppe til langt på natt, for å lese i fred.

Men det er ikke lett når døren til tjenestejentenes værelse står åpen heller. Etter tre år mottar Henrik et brev fra byfogden i Grimstad. Der står det at tjenestejenten Else Sophie oppgir ham som barnefar. Fogden vil vite om dette stemmer.

Henrik vedkjenner seg farskapet, men sår samtidig tvil: I det aktuelle tidsrommet har tjenestejenten også hatt omgang med andre mannspersoner, hevder han. Likevel våger han ikke bestemt å frasi seg det anmeldte farskapet, fordi han dessverre har hatt legemlig omgang med henne. Dette skyldes hennes fristende oppførsel og det at deres tjeneste hos apotekeren ga dem anledning …

«… uagtet Pigens Samqvem ogsaa med andre Mandspersoner paa den vedkommende Tid, tør jeg ikke bestemt fralægge mig bemeldte Paternitet, da jeg desværre med hende har pleiet legemlig Omgang, hvortil hendes fristende Adfærd og samtidige Tjeneste med mig hos Apotheker Reimann i lige Grad gav Anledning … »

Nå skrur vi tiden frem til det 21 århundre

Mai 2021

Da sommeren var i emning og naturen sto i full blomst, dro jeg til Grimstad for å vandre i unge Ibsens fotefar. Dette var i forbindelse med min nye roman, hvor jeg følte et sterkt behov for å komme tettere innpå vår store dikterhøvding og hans inspirasjonskilder.

Åh, du veid, Henrik var jo ikke så god å stagge

Men jeg oppdaget fort at Ibsens ettermæle i Grimstad, selv den dag i dag, er preget av farskapssaken der tjenestejenten Else Sophie Birkedalen i 1846 fødte et barn som hun ga navnet Hans Jacob Henriksen.

Henrik, som var ti år yngre enn Else Sophie, vedkjente seg farskapet, men han ville ikke ha noe med sønnen å gjøre, bortsett fra at han betalte lovpålagte bidrag frem til gutten var 14 år og kunne forsørge seg selv.

Samtidig skal det heller ikke stikkes under en stol at Henrik Ibsen, tidlig i sin karriere, gjentatte ganger ble truet med tvangsarbeid for ubetalte barnebidrag. Så det er rimelig å tro at disse vanskelighetene satte spor i det senere forfatterskapet.

I det hele tatt må tenåringen Ibsen ha opplevd nok av familiedramaer å hente inspirasjon fra. Ikke minst hjemmefra med tvangsauksjoner og økonomisk ruin, som sikkert medførte en del krangel og bekymringer.

Men også apotekerfamilien Reimanns hadde sitt å slite med, og det kan ikke ha vært uproblematisk å leve så tett på dem som det Henrik gjorde.

Etter tre år ble apoteket solgt til Henriks fire år eldre kollega Lars Nielsen og flyttet til en større bygård. Der fikk han beholde sin stilling og kunne puste lettet ut. Ja, ikke bare det, nå var han blitt uteksaminert apotekermedhjelper, samt at han fikk sitt et eget værelse, større frihet og høyere lønn.

Da bodde Else Sophie hjemme hos sine foreldre. Det å få barn utenfor ekteskap ødela hennes liv fullstendig. Hun så aldri Ibsen igjen, og døde mange år senere som et «fattiglem», i en alder av 74 år. Ifølge Robert Fergusons biografi om Henrik Ibsen 1996 s. 394, skal en eldre kone som prøvde å hjelpe Else Sophie ha spurt henne om hvordan «ulykken» skjedde, hvorpå svaret ble: «Åh, du veid, Henrik var jo ikke så god å stagge».

Å besøke Ibsenmuseet er selvfølgelig et must når man er i Grimstad, og her fikk min familie og jeg en fantastisk omvisning av museets guide. Og det var flott å se at så mye av interiøret er bevart i Lars Nielsens apotek, i det apoteket hvor Henrik vokste som kunstner. Der han kom med i leseselskapet og ble mer utadvendt og fikk intellektuelle venner som oppmuntret ham til å skrive.

Ved dette bordet skrev Henrik sitt første verk «Catilina». Dette verket handler om en romersk statsmann som ønsket gjenreise Romas storhet, men hans politiske ambisjoner ble blant annet hindret av erotiske feiltrinn som han hadde begått. Kanskje ikke å undres at Henrik følte en viss sympati med denne romeren og klarte å leve seg inn i hans rolle.

Dessuten var Henrik preget av de revolusjonære aktivitetene i 1848. De brøt først ut på Sicilia, og spredte seg raskt til Frankrike og videre gjennom Europa. Dette var en voldelig reaksjon på de store forandringene kontinentet hadde gjennomgått de siste tiårene. Den raskt voksende borgerklassen ønsket å øke sin representasjon i sine nasjoners styresett.

Henrik hørte sikkert at urolighetene hadde nådd København, Stockholm og Christiania. Noen omtalte dette som pøbelopptøyer uten noe ideologisk innhold av betydning eller noen politisk ledelse. Men i stykket fremstilles Catilina som en karismatisk leder som utfordrer korrupsjonen i den verden han lever i.

Også Henriks omgangsvenner Ole Schuleruds, Gunder Holst, Jacob Holst og Christopher Due lot seg begeistre av Catilina mens de drakk punsj og diskuterte politikk med ham.

To år senere ble Catilina utgitt i Christiania under pseudonymet Brynjolf Bjarme. Siden ingen forlag ville gi ut boken, ble utgivelsen bekostet av Ole Schulerud. Han brukte en liten arv til formålet. Likevel ble salget dårlig, og mye av opplaget endte som makulatur.

Apotekets kunder påvirket Henrik

Ved denne skranken kom Henrik ofte i snakk med kundene, noe som satte skapergleden i sving hos den unge kunstneren. Både i form av dikt og tegninger. Blant annet hadde han utstilt et oljemaleri, et portrett som han malte på papp «af den gamle søulk». Alle mente at det lignet godt. Det sto bestandig på reolen. Det forestiller losen Svend Hanssen Haaø fra Håhøya.

Det sies at Henrik hadde stor interesse for losene og fiskerne. Det var tydelig når det gjaldt Svend Hansen Haaø. For denne flinke og djerve losen, med sitt værbitte utseende, begeistret ham med sine fortellinger om krigsbegivenheter og sjøvesenet.

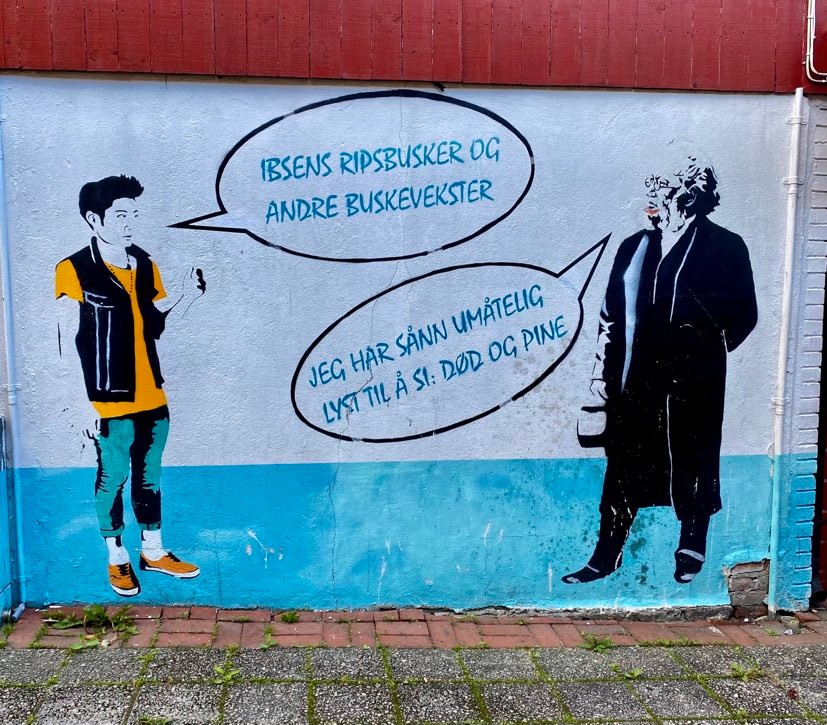

Det skal være fra ham Henrik fikk ideen om å skrive sitt makeløse dikt «Terje Vigen», som har gjort byen Grimstad og omegn kjent.

Terje Vigen er et episk dikt, skrevet av Henrik Ibsen i 1861. Det ble første gang publisert i heftet Nytaarsgave for Illustreret Nyhedsblads Abonnenter for 1862, og ble senere gjenutgitt i hans eneste diktsamling Digte fra 1871. «Terje Vigen» ble i 1890 utgitt separat med illustrasjoner av Christian Krohg.

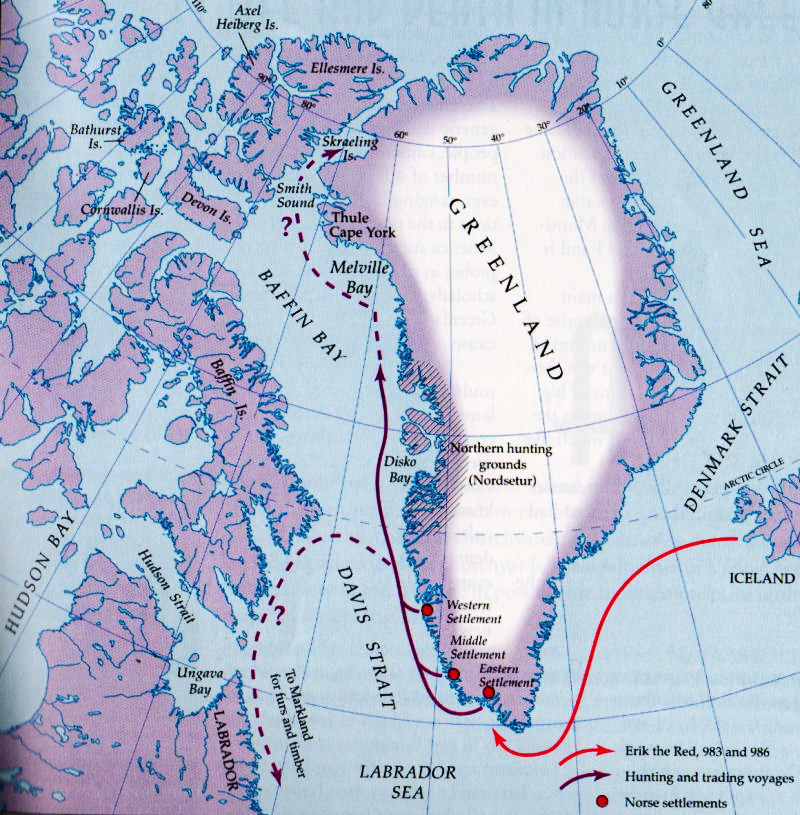

Diktet bygger på fortellinger fra sørlandskysten under Napoleonskrigene. På denne tiden var Danmark-Norge i krig med blant andre England, som hadde innført handelsblokade og dermed kuttet all kontakt mellom Norge og Danmark. Dette medførte hungersnød i Norge. Diktets hovedperson ble tatt av et britisk marinefartøy og sendt i krigsfangenskap i Storbritannia, den såkalte «prisonen»

Diktets åpningsstrofe:

«Der bode en underlig gråsprængt en

på den yderste nøgne ø …»

Å besøke Håøya sto høyt på ønskelisten min, sammen med Hesnesøya, øya der Henriks bestefar druknet. Både Hesnesøya og naboøya Kvaløya kunne ha vært «den yderste nøgne ø» der Terje bodde. Dette spørsmålet genererer en endeløs debatt blant lokalbefolkningen.

Derfor ønsket vi å se dem alle. Følgelig var vi innom Grimstad Turistkontor og leide en 15 fots Pioneer-jolle med åtte hk påhengsmotor og redningsvester. Veldig praktisk og godt tilrettelagt.

Så satte vi kursen for hvor losen Svend Hanssen Haaø bodde. Og Terje Vigen, om han noen gang var et genuint levende menneske.

Selve overfarten gikk helt uten dramatikk, og vi fant oss en lun vik hvor vi gjorde strandhugg ved det gamle los-samfunnet.

Heldigvis var det ingen skilt med privat brygge å se der hvor vi fortøyde båten. Det var åpent og trivelig å ferdes der ute, med unntak av naturens egne stengsler, i form av tett villnis og kløfter i berget med rullesten i bunnen.

Hit ut kom også Henrik for å høre losens historier fra gamle dager. Mange av disse var selvopplevde. Under Napoleonskrigene, med britenes blokade av landet, hadde Svend Hanssen Haaø tatt seg over til Danmark flere ganger for å kjøpe korn og andre matvarer.

Men i våre dager kan dette virke ubegripelig. I havet er det fullt av fisk og østers.

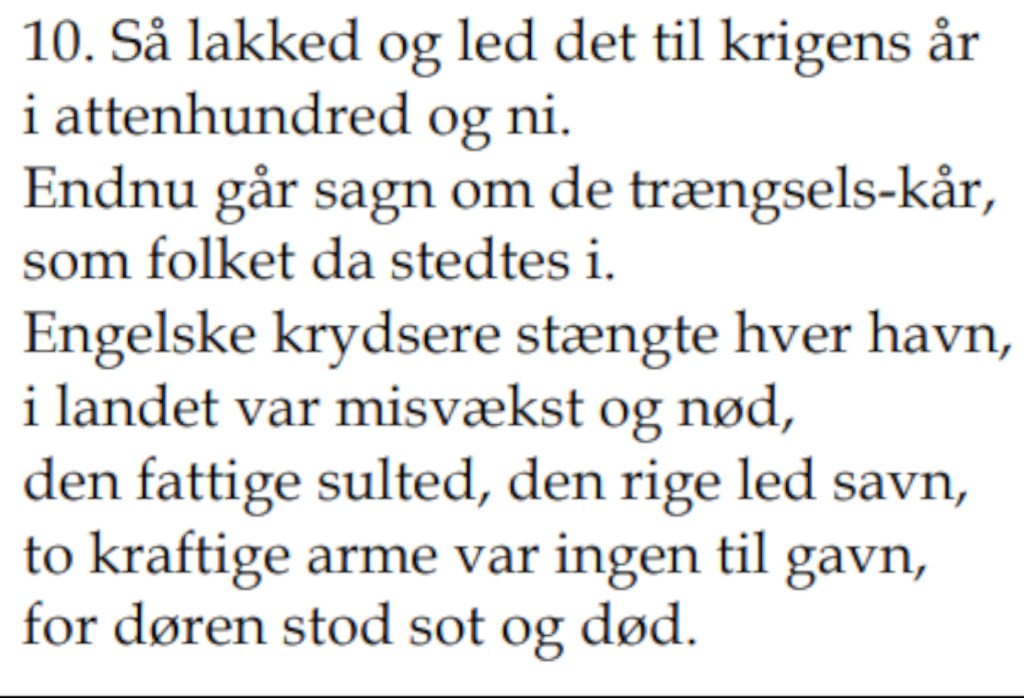

Terje Vigen vers 10:

Våren 1808 kom Danmark-Norge også i krig med Sverige. Sommeren ble våt og kald, og det ble misvekst i landet. I tillegg slo sildefisket feil. Allerede i oktober gikk de militære matlagrene tomme. Folk ble syke av forråtnelsesfeber, og mange døde av den. Fra begynnelsen av januar 1809 til midten av februar, lå det tykk is i alle havner øst for Lindesnes.

Så ja, Henrik Ibsen overdrev ikke.

Men nå var Håøya kledd i sommerskrud, og alt var bare fryd og gammen.

Sejl og mast lod han hjemme stå …

Men hvorfor rodde folk til Danmark når de kunne seile?

Terje Vigen vers 12:

Egentlig ligger svaret i selve teksten. Det gjaldt å gjøre seg så liten og ubetydelig som mulig. En seilbåt er lettere å oppdage enn en båt uten seil. Den engelske marines skip hadde personell i mastetoppen som fulgte nøye med, og kunne dermed oppdage et lite seil på lang avstand.

I tillegg dro «Terje Vigen» og losen Svend Hanssen Haaø ut på havet i dårlig vær. For å ro over til Danmark. Gjerne om vinteren når de fleste lå i vinteropplag. Ofte i åpne båter, som vist på bildet.

Vi turte ikke å gå langt ut fra land i Pioneer-jolla som vi leide. Bølgene gikk så grove at vi måtte gi opp planen om å besøke de andre øyene; Hesnesøya og Kvaløya. Vi måtte snu tilbake til den trygge havnen i Grimstad. Jolla vår var 15 fot. «Terje Vigens» båt var muligens 12. Sånt står det respekt av!

Når det er sagt, så mener jeg bestemt at Henrik Ibsens dikt om Terje Vigen fortjener å leve videre i vår folkesjel. Og det å gå i unge Ibsens fotefar, i sørlandsperlen Grimstad, ble såpass inspirerende at jeg fikk skrevet «Stormens hjerte»; min roman om Terje Vigen.

PS. Se på den underlige skyen bak meg. Det føltes nesten som Ibsen var til stede. Men da må man tro på «Gjengangere», og det er en helt annen historie …

Takk for meg.